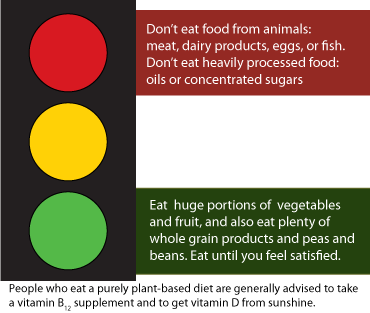

To lose weight without feeling hungry, all you have to do is go ape, go wild, and eat plants. The easy and healthy way to lose weight is to fill up on high-fiber, low-fat plant foods and avoid animal-based foods and oils. It’s also important to avoid processed foods that are high in fat or concentrated sugar but low in fiber. The only essential nutrients that plants don’t provide are vitamin B12, which comes from bacteria, and vitamin D, which your body produces naturally when bright sunlight hits your skin.

A diet based on low-fat, unrefined plant foods satisfies your hunger on a reasonable number of calories. The high carbohydrate content of the diet also helps you feel more like exercising and even helps you burn more calories at rest. It’s hard to “fatten” on a high-carbohydrate diet, because about 30% of the calories are wasted when the body converts sugar to body fat.

In other words, the human body is well-adapted to a low-fat diet based on unrefined plant foods. We get weight problems, as well as other health problems, when we eat foods that are low in fiber and/or high in fat, such as animal-based foods and processed foods.

Why does “going wild” and eating a more natural diet help people lose weight? Wild animals can’t count, so they never count calories. Nor do they ever sign up for step aerobics classes. Yet wild animals stay at a normal healthy weight while eating whatever they want, whenever they want, and doing whatever they feel like doing. Their secret is that they eat the right kinds of food. They eat the diet that their bodies are well adapted for eating. Thus, they can depend on their appetite to control their weight. Likewise, most overweight people could easily control their weight if they simply stopped eating the kinds of food that are making them fat and filled up on low-fat, high-fiber plant foods instead.

A low-fat, high-fiber diet is the diet that the human body is well-adapted for eating. When we eat that kind of food, our appetite can regulate our weight naturally. Yet most people try to control their weight while continuing to eat the kinds of food that made them fat. Instead of correcting the kind of food they eat, they try to correct the size of their portions, an approach that is practically doomed to fail.

Calories are energy

The calories in our food are really what a chemist calls “kilocalories.” Each kilocalorie represents the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by 1 degree centigrade. Just to avoid confusion, I’ll refer to kilocalories as “calories.”

All of the energy in our food came originally from sunlight. Green plants use the energy from sunlight to turn water and carbon dioxide into a simple sugar called glucose.

The plant can then use the glucose for several different purposes. It converts some of the glucose back to carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy that the plant then harnesses to use for other purposes.

The plant can also use the glucose as a raw material for making other things, including other carbohydrates (sugars, starches, and fiber), amino acids (the building blocks of protein), and fats.

The energy that was used to make these big molecules out of smaller ones is stored in the big molecule. It will be released when the big molecule is broken down again into small molecules.

Calories in food

All of the calories in our diet came originally from plants. Plants make big molecules that have a lot of extra energy embedded in them. Animals eat those big molecules and convert them back into small molecules again. This releases the embedded energy, which the animals then capture and use for their own purposes.

Some kinds of molecules have more energy embedded in them than others have. Although fiber has energy embedded in it, our bodies can’t break the fiber down into smaller molecules. As a result, fiber provides practically no calories. On the other hand, our bodies can digest sugar and starch, which provide 4 calories per gram. If we eat more protein than we need, our body converts it to sugar and burns it for energy. Like sugars and starches, proteins provide about 4 calories per gram. On the other hand, fat provides about 9 calories per gram.

Why does a gram of fat contain more than twice as many calories as a gram of sugar or starch? The answer becomes obvious when you look at their chemical structure. Carbohydrates got their name because they are “hydrated carbons.” They contain one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms (the equivalent of one water molecule) for each carbon atom. In contrast, fats contain almost no oxygen at all. They are mainly a long string of carbon, studded with hydrogen. It will take a lot more oxygen, and a lot more “oxidation,” to turn the fat into carbon dioxide and water. All that extra oxidation will release more energy, which we measure in calories.

Plants tend to be high in fiber, and their stored energy tends to be in the form of starch. Food that comes from animals never contains any fiber, and it rarely contains digestible carbohydrates. In animal products, the stored energy tends to be in the form of fat.

Why do plants usually store starch while animals store fat? It’s partly because the process of converting sugar to fat is wasteful. You actually burn up some calories in the conversion process. But this loss of calories is a great investment if you would have to waste energy carrying your energy stores around with you. A pound of body fat contains about six times as much energy as a pound of starch and water. The only plant parts that are normally high in fat are nuts and seeds, which of course are built for travel.

How your body burns calories

To lose a pound of body fat, you have to burn up 3500 more calories than you get from your food. The easiest way to do that is to switch to a diet that makes you feel full on fewer calories, so that you won’t overeat, and that encourages your body to burn extra calories. A low-fat, high-fiber diet helps you do both.

Sugar and starch

Your body’s favorite fuel is glucose. The cells in your body use oxygen to turn glucose back into carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy in the process. The cell then captures some of this energy and uses it for many different purposes.

You can find glucose in some kinds of food, such as grapes. However, most of the glucose that the body uses comes from the breakdown of other carbohydrates. Starch breaks down into pure glucose. Table sugar breaks down into a 50:50 mixture of glucose and another simple sugar, called fructose. High-fructose corn syrup is a 45:55 mixture of glucose and fructose.

Your body can store some glucose by converting it into a starch called glycogen. When the level of glucose in your bloodstream drops too low, the body reacts by converting some of its glycogen back into glucose.

If you eat some extra sugar, your body will replenish your stores of glycogen. Once you have made enough glycogen, it could convert the extra sugar to fat, but it would waste 30% of the calories in the conversion process. So your body prefers just to burn up a few extra calories if you are eating a starchy diet. This “margin for error” can mean the difference between staying slim and gaining weight.

Protein

Protein can also be burned to produce energy. Your body can take the amino acids that are the building blocks of protein and burn them for energy, in a chemical process called the Krebs cycle. Your body can even convert most of the amino acids to glucose, or blood sugar. The others can be converted to other kinds of fuel, such as ketone bodies or fatty acids.

Unfortunately, there are two downsides to using amino acids for energy. Once the body has broken an amino acid down and burned it for energy, that amino acid won’t be available for use in making new proteins. Also, converting amino acids to sugar releases additional waste products, including ammonia and sulfuric acid. If you burn a lot of protein for energy, then your liver and kidneys will have to deal with a large amount of waste. That’s why high-protein diets are bad for the liver and kidneys.

Your body has no convenient way to store excess protein. So if you eat any more protein than you need, your body will just burn it for fuel. In other words, excess protein in the diet is really just a dirty source of sugar. When you try to figure out how much protein people need, you have to consider how much of the protein they eat is being used as protein and how much is being converted to sugar for use as calories. People who eat a lot of carbohydrate need surprisingly little protein.

People who eat high-carbohydrate diets end up burning less protein as fuel. The higher the carbohydrate content of the diet, the less protein people will end up burning for energy, and the less ammonia and other toxic byproducts they will produce. That’s why a high-carbohydrate diet has been recommended for decades for people suffering from liver or kidney disease.

When people are starving, they will end up using their body’s structural proteins for fuel. It’s like burning your furniture and the siding of your house for fuel. Although starving people end up losing protein from the body, the problem results from not eating enough calories, not from eating low-protein food. Only under extremely unusual circumstances do people who are getting enough calories suffer from a shortage of protein, or of any of the essential amino acids.

Fat

Your body can also burn fat for fuel. However, it prefers to burn the available sugar first, saving the fat for later. If your body runs low on sugar, such as during starvation or during a low-carbohydrate diet, you will end up burning a lot of fat and protein for fuel.

If you eat more calories than you need, your body prefers to burn the carbohydrates first and then store the leftover fat. The fat can go straight to your fat cells. You lose only about 3% of the energy when you convert dietary fat into body fat. That’s why fatty diets are so fattening.

Some people try to lose weight by eating low-carbohydrate diets, which means that they get a larger percentage of their calories from fat. People often lose several pounds during the first phase of the low-carbohydrate diet, because their body uses up its stores of glycogen. This releases several pounds of water, which is then lost through the kidneys. This weight will come right back as soon as the person starts eating normally again. In the longer term, the low-carbohydrate diets “work” by making the body think it’s sick or starving. The body responds by suppressing the appetite.

Why did Morgan Spurlock gain so much weight from eating a fast food diet in his documentary Super Size Me? The food he ate was very high in calories, and it contained a lot of fat as well as a lot of sugar. His body probably used the sugar for his immediate energy needs, and the leftover fat was efficiently stored in his fat cells.

Maintaining a normal weight

How do wild animals manage to maintain a normal weight without counting their calories or signing up for step aerobics? They rely on built-in mechanisms that regulate their weight naturally. When you travel around the world, you notice that some human populations also seem to stay at a healthy weight naturally. These populations tend to base their diet on a starchy staple such as rice or corn or potatoes and eat a lot of vegetables and fruit. Unfortunately, when people from those naturally slender populations move to the United States and start eating the rich and fatty standard American diet, they develop the same weight and health problems as the rest of the U.S. population. So the simple solution to our weight problems is to switch to the kind of diet that is eaten in places where people stay naturally thin.

The societies where people stay naturally slim tend to consume a low-fat, high-fiber, plant-based diet. They usually depend heavily on some starchy staple, such as rice, corn, or potatoes. They also eat lots of other vegetables and fruit. This low-fat, high-carbohydrate, high-fiber diet works in several ways to help regulate weight. It affects both the “calories in” and the “calories out” side of the weight loss equation.

As I explained above, fat is a concentrated energy source. Not only does fat contain 9 calories per gram (as opposed to four calories per gram for carbohydrates and protein), fat repels water. In contrast, carbohydrates have only 4 calories per gram and absorb water. That’s why a starchy food like rice end up providing only about 1 calorie per gram of food as it is served.

The human appetite is well adapted to a diet that is low in fat and high in fiber. When overweight people switch to a diet like that, they tend to lose weight effortlessly, because the sheer volume of the food helps to satisfy their appetite. The extra work that would be involved in overeating doesn’t feel worthwhile.

Besides reducing the number of calories that people take in, a low-fat plant-based diet also tends to boost the number of calories that people burn up. That’s because most of the calories are coming from starch. A starchy diet tends to make the body more sensitive to the hormone insulin, which means that the glucose that is released when the starch is digested goes quickly into the body’s cells. When laboratory mice are switched from a fatty diet to a starchy diet, they end up spending a lot more time voluntarily running on their exercise wheels. Similarly, people who switch from a fatty diet to a starchy diet end up burning extra calories, often without even realizing it. They fidget more, or produce more body heat.

Even though a healthy diet is high in carbohydrate, those carbohydrates should be more or less in their natural form. The human body was designed to eat plants, including some sweet fruits. The sugar in those foods is bound up with fiber and water and other good things, such as other nutrients and antioxidants. In contrast, processed foods such as candy and soft drinks contain purified sugar, without any fiber or other added nutrients. So the ideal human diet would be high in carbohydrate, but not high in added sugars.

Photo by the Italian voice